New Vrindaban Days – Chapter 4

New Vrindaban Days

As New Vrindaban enters its 50th anniversary (1968 to 2018), I wrote this series of articles for the Brijabasi Spirit in an attempt to give the reader not only an “understanding,” but more importantly a “taste,” of what life in early New Vrindaban was like – through the stories of one devotee’s personal journey.

The title of the series, “New Vrindaban Days,” is in tribute to the wonderful book “Vrindaban Days: Memories of an Indian Holy Town” written by Howard Wheeler, Hayagriva Das. He was one of Srila Prabhupada’s first disciples, a co-founder of New Vrindaban, and, a great writer. As with Hayagriva’s book, this series focuses on a period of time in the 1970’s.

I would also like to acknowledge and thank Chaitanya Mangala Das, for spending untold hours assisting me in refining my writing for your reading pleasure.

I have been asked to describe certain aspects of early New Vrindaban Community life such as the nature of the austerities, what it was like for a new person coming here, cooking, anecdotes about particular devotees, etc.

I attempt to tell these stories in some semblance of a chronological order, beginning with my first meeting with devotees in 1968, leading to my arrival in New Vrindaban in late 1973 and carrying through to the official opening of Srila Prabhupada’s Palace in 1979.

Advaitacharya Dasa

Chapter 4: Fired Up – We Depend on Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Chandra

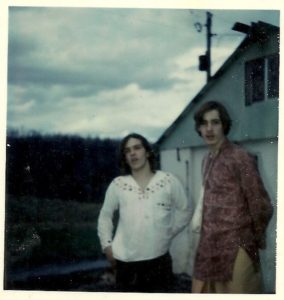

Bhakta Emil (pre Advaitacarya Das) & his brother, Bhakta Bill, at Bahulaban in New Vrindaban, early 1974.

It is December 1973 and I have been chanting Hare Krishna for the better part of two years. I have just returned to NYC where I live, after visiting New Vrindaban for the first time. The idea is that I will get my belongings and return to New Vrindaban where I will officially join the Hare Krishna Movement. At home I do rapidly begin to experience life shaking “movements” but they are neither taking place in a motor vehicle nor are they part of the spreading of the chanting of Hare Krishna.

World travelers are familiar with maladies that carry exotic names like India’s “Delhi Belly,” or Mexico’s “Montezuma’s Revenge.” At the time I am nowhere near being a world traveler nor am I familiar with the above mentioned exotic labels. I have experienced severe stomach disorders in my twenty years but nothing like those that consume me for the better part of the next two weeks. While visiting New Vrindaban I may have heard mention of issues with the drinking water, but this is beyond an issue. For two weeks I cannot even think of leaving my bed and bodily fluids are leaving my body through every avenue of exit faster than I can put them in.

When I’m finally able to get on my feet, I call Kirtanananda Swami and let him know why I have been delayed. He gets a good chuckle knowing exactly what I am going through. Right before we hang up he asks, “Do you think you could bring a few things we need?” I tell him sure and he lets me know he will make me a list.

The next day I call back and am shocked to get a list that includes sheet rock, insulation, and a host of various building materials, as well as bulk spices, rice, and other food items. It takes me days to do the shopping and there is so much I have to rent a trailer to get it there. The Swami makes it clear that he will be happy with whatever I can get off the list but I am trying to make a good impression and anxious to help build New Vrindaban in any way I can, so I get everything he’s asked for. The total bill comes to over two thousand dollars – or more precisely – every penny I have in the world.

When we pull up to the bottom of the driveway at Bahulaban, it’s like Christmas. Many of the devotees I had been hauling firewood over the ice with three weeks earlier come to greet us. Bhakta Mark (Madhava Ghosh), Bhakta Busby (Haridhama), Bhakta Dennis (Damodara Pandit), and Bhakta George (Jalakholahali) empty the trailer and carry the supplies into the temple building.

We quickly find out in the three weeks we have been gone the single men have moved three miles up the road to live in the isolation of the original Vrindaban farm. The look on my brother Billy’s face belies the fact that he is not happy to be leaving us and going up the road. None of us expected this.

Eventually I make it up to the Swami’s cabin and ask him what living space I should move my stuff into. He tells me that I should go to the temple and ask for the acting temple president, Radha Kanta.

When I enter the building I find two devotees sitting at the base of a wall with one playing a harmonium and the other chanting. I sit for a while listening to them and after a few minutes they realize I am waiting to speak to them and finish up.

“Excuse me. The Swami told me I should find Radha Kanta.” I say.

The devotee who had been chanting answers back in the heaviest southern drawl this NYC kid has heard on anything other than a TV set. “I’m Radha Kanta. What can I do for you?”

“My girlfriend and I have just moved here. The Swami told me to ask you where we should live.”

Radha Kanta looks stunned. “He told you what?”

“To ask where we should live.”

He turns his head to look at Devakinandana, the harmonium player. He turns back to me.

“He told you to ask me where you should live?”

“Yes.”

Again he turns to Devakinandana, and then back to me, “SON – OF – A – B…CH. He knows there’s no place for you to live.”

I make it back up to the cabin with the news. It seems that there is an abandoned box truck in the parking lot and it is suggested my girlfriend and I stay in the truck until an apartment comes vacant. Hopefully it will only be a few days.

Truth be told the box truck is a bit rustic and even a tad romantic. We have just moved from New York City. Knowing New Vrindaban is more or less a frozen tundra we arrived loaded up with plenty of blankets and warm clothes, all of which are in the truck with us. Throughout the night we are so cold we put everything we own on top of us. It is still unbearable. Thankfully we are still alive when 2:30 AM rolls around and it is time to get up for the morning program.

Later, I make a case for wanting to stay alive long enough to render some service and we are given a small lantern like heater to bring to the truck for our second night. Success! It casts a beautiful light and actually warms the truck. We get o good night sleep but wind up waking up late for the morning program. I rush out of the truck to the bath house.

What is called the “bath house” is actually the furnace room under the temple building. The temple building at Bahulaban is a farmhouse over 100 years old. When I say the words “furnace room” it is not like any furnace room that most of the readers have ever seen. The door is made of old boards barely nailed together that drags along the ground as I open and close it. Inside is a dirt floor and the furnace itself is a large old wood burner that requires large chunks of logs. The walls are stone blocks and the taller devotees have to bend over inside the room so that they won’t bang their head on the rafters. On the dirt floor against the stone wall there are two wood pallets which I have to stand on to be out of the mud while I bathe. A large red plastic barrel, purchased in bulk from a Pittsburgh pickle factory, holds the ice cold water I will scoop and pour over my head.

But, enough of that. It is 4 AM and I am late for Mangal Aroti. I drag the door open and a devotee rushes out past me. He seems to give me a strange look on his way past. I think it must be because I am even later than him. I remove my muddy boots, hoping to keep my clothes out of the mud, and climb up onto the pallet. I plunge the cut out plastic gallon milk container into the water and cringe as I pour bucket after bucket over my body. The one off the top of my head makes it feel as if my head has cracked in half. The one that runs down my back makes my entire body rock. I would describe what the additional scoops do to me but by that time I am so traumatized that I don’t comprehend anything else that is happening. Afterwards, in a state of pain and delirium, I desperately clutch a towel to dry myself, get dressed and run up stairs across the snow and ice to enter the temple building on the ground level.

Along the side of the temple building is the Tulsi greenhouse. I enter the greenhouse darting the twenty feet in the direction of the well that lies toward the back of the room. To the left is the side door into the actual farmhouse. The first room I step into is the prasadam hall. As I go through the side door, just to my right is a small doorway covered with a lotus arch that leads into the temple room, an extension that has recently been built onto the farmhouse. I can hear the Samsara Prayers are just ending. At least I will catch 2/3 of the Aroti. Instead of going to my right and into the temple room, I make a left turn and rush to a mantel piece where a bowl of tilak sits just below a large mirror.

I stick my finger into the bowl and raise my eyes to the mirror. In my reflection I do not find myself but instead what seems to be Al Jolsen in blackface. I am completely covered in an oily soot with the only bits of white appearing when I blink my eyes. I try rubbing it off, to no avail. I’m in a panic. I decide to pull my chadar down over my face and run back across the prasadam room, going under the arch and through the six foot long walkway, into the temple room.

The temple room is about twenty five foot square. As I enter the room, the altar of Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Chandra is to my left and quickly behind me as I pay my obeisances. I rise up, chanting with the other devotees, careful to keep my face completely covered by the hood created by my chadar. At the end of the Aroti I rush out before the rest of the program and back to my truck chalet.

Again I have to make a case for staying alive through another night without succumbing to poisonous fumes. It is suggested we leave our belongings in the parking lot truck and sleep each night on the floor of the incense warehouse, until a place comes available. As we slept in the incense warehouse during our visit three weeks before, we not only feel comfortable, but we are also fairly confident we will make it through the night without dying.

I have no discernible talent so I spend the first few days with my brother, Bhakta Bill, and Bhakta Atticus (Tapanacharya Das) pulling mud down the drive way. We are not pulling mud with a back end loader or a bulldozer. Instead the devotees have furnished us with planks of wood about 24 inches long through which they have drilled a hole in the center. Through the hole they have wedged a broom handle and tried nailing them in. We are using these make shift squeegees to drag mud from behind the cow barn, across the patio, down the driveway and across the road. In total the distance is about the length of half a football field. Progress is more than just slow.

Soon enough everyone realizes how futile it is and I am sent to help in the wood shed. The wood shed is a tin roof on poles made of the trunks of small trees sitting under a large willow tree and extending out off the side of a ten foot by ten foot cinder block building painted ugly green, which serves as the women’s bath house.

Under the roof there is a “buck saw,” an implement wielding a thirty inch spinning saw blade used to cut logs into eighteen inch lengths. After the frozen logs, which have been dragged in by the horses, are cut they are then split into sizes small enough to fit into the wood stoves used in different locations. Four barrels split fine for the Deity kitchen, fifteen pieces to be carried up the hill to “householder heights,” eight pieces for the Swami’s cabin, and of course – some choice, dry wood for the nice people now sleeping on the floor of the incense warehouse.

Settling in over the next couple of weeks is made easier by the fact that the incense warehouse has its own wood stove. Not being familiar with what a wood stove should actually be, I am completely unaware that the one we have is really no more than a large tin can with a slide open top. A top that I might add, in retrospect, is obviously defective.

I have fallen into a comfortable groove. Each day in the shed I am sure to pick the choicest wood for our stove. After the brahmacari working in the warehouse leaves for his three mile walk to the Vrindaban farm each evening, I bring our wood to our chalet. The evening program is attended by all of the devotees. As a part of my nightly routine I first rush to the warehouse to fill the wood stove with hot burning locust wood. Next I proceed to the bathhouse, and then to the temple for Tulsi Puja. I am comfortable knowing after the program – and hot milk prasadam – I will return home to a spot on the floor of the warmest, most fragrant place in all of New Vrindaban.

On this snowy, frozen night I enter the bath house to find a new devotee from the Boston temple standing in his Brahmin underwear on the pallet. Uttamauja is the largest devotee I have ever seen, standing well over six feet tall and weighing at least 350 pounds. I undress, place my clothes on the shelf and make my way to the pallet. As the ice water splits my head in half the door of the bath house flies open and I look up to see Amburish, the head of the cow barn, standing in the doorway with a look of terror on his face.

“FIRE!” Amburish screams.

“Where?” I plead.

“Incense warehouse,” he responds.

Along with my frozen head, my heart now also shatters. I leap from the pallet and in a panic reach for my clothes. When I pull the pants up I soon realize that I am swimming in Uttamaujas size 60 jeans. I grapple to hold the pants up and rush out barefoot into the night. Devotees stream past, going to and from the cow barn carrying buckets of water. I run to the burning building. The Swami is outside telling everyone to stand back. I can’t. I’m drenched not only in ice cold water but also in guilt. I know that this is the only source of revenue for the entire community and that I am responsible for the flames now soaring fifteen feet in the air. Ignoring his pleas I snatch a bucket of water from the hands of a nearby devotee, rush to the door and heave the water into the flames.

Unbeknownst to me, the essential oils burning inside do not mix well with water and although the flame initially dances briefly away, it comes roaring back, searing off my eyebrows and causing the skin of both of my ears to immediately blister. The devotees scream for me to stand back while the fire consumes the entire building and our rag tag fire line stands forlorn under the moon and frozen trees on the ice and snow.

Later, I sit weeping in the Swami’s cabin. The community electrician, Gadadhara, is in the room. Both try to console me but I am devastated.

“Bhakta Emil, it’s alright,” the Swami says.

“It’s not alright. The whole community is dependent on the incense business.” I cry.

“Bhakta Emil. We don’t depend on the incense business. We depend on Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Chandra.”

I can sense he is not blowing smoke. He believes it. He wants me to believe it. He is accepting of me and the guilt I am wallowing in leaves me completely.

“You and your girlfriend can stay with Gadadhara and Sarveswari. They have a loft in their apartment.”

Luckily, all we personally own is still in the truck, so we have bedding and clothing. We trudge up to the top of the hill and enter the “apartment” Gadadhara has led us to. It is a single room no bigger than 12 foot x 12 foot with barely anything in it. He leads us to the “loft” – a 2.5 ft. wide shelf mounted ¾ of the way up the wall. Gadadhara sees the look on my face.

“Welcome to householder heights,” he says.

Did you miss any of the previous chapters? Click the links below to catch up:

Chapter 1: Every Journey Begins With a Single Step

Chapter 2: Srila Prabhupada – Jaya Radha Madhava

Chapter 3: Captured by the Beauty of Sri Sri Radha Vrindaban Chandra

Stay tuned for Chapter 5: The New Vrindaban Landscape – January 1974